Though less forbidding than it once was, Papua New Guinea remains one of the planet’s wildest places. An off-the-grid guide for travelers who still like their creature comforts.

Though less forbidding than it once was, Papua New Guinea remains one of the planet’s wildest places. An off-the-grid guide for travelers who still like their creature comforts.

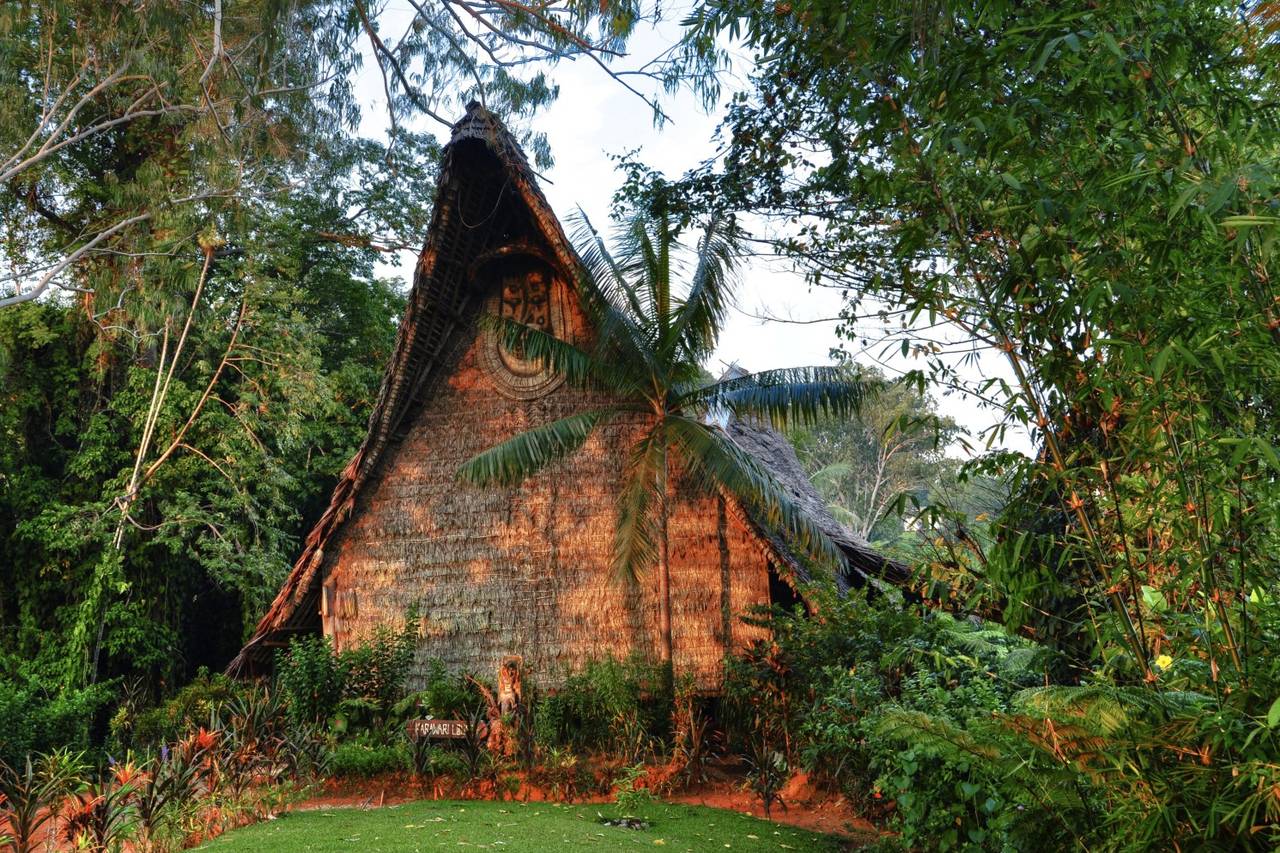

In a bush plane buzzing high above the jungle of central Papua New Guinea, I peered through the windshield from my passenger seat. Below, a dense carpet of green spread in every direction. Not a single road or sign of humanity interrupted it—only the Karawari River, winding through the trees like a thick, glittering snake. Suddenly, a few inches from my face, a hairy, mouse-colored spider the size of a toddler’s hand emerged from a crevice between the plane’s windshield and instrument panel. As it scuttled across the dials, the pilot grabbed his flight-log clipboard and delivered a mighty wallop to the intruder. It crumpled into a fuzzy wad between my shoes.

It was a near-perfect illustration of a lesson I’d learn repeatedly in Papua New Guinea: No matter how peaceable things seemed there, the wildness found a way in.

Most people would be hard-pressed to find Papua New Guinea on a map. The eastern half of a bird-shaped island off the northeastern tip of Australia (the western half belongs to Indonesia), it’s about as far off-the-beaten track as you can get. Even those who have heard of the country likely only know it as a menacing backwater where young explorer Michael Rockefeller was devoured by cannibals in 1961. Can you blame tourists for staying away?

Even now, the country remains largely undeveloped. Much of the terrain is formidable, with thickly forested peaks rising as high as 15,000 feet. Many Papuans work as subsistence farmers or herders, residing in primitive villages, practicing the same tribal customs and speaking the same languages (more than 800 distinct tongues) as they have for centuries.

In the 1970s, when I was a child, my geologist uncle lived in Papua New Guinea with his family, apparently undaunted by cannibals. He’d send photos of iridescent blue butterflies, wildly spotted possums and tribesmen clad only in paint and leaves—a real-life Land That Time Forgot sans dinosaurs.

When I finally went myself, last summer, I realized my presumptions about the place were shamefully outdated. Flying into Port Moresby, the country’s capital, I passed over office towers and highways. I didn’t stay in the capital—only stopped to change planes for Mount Hagen, a town in the Central Highlands—but if I had, I could have booked the Port Moresby Crowne Plaza or Holiday Inn Port Moresby, both frequented by business travelers calling on one of the many foreign-owned mines or drilling rigs operating throughout the country. Still, beyond the capital and a few other highly populated areas, creature comforts in Papua New Guinea remain relatively rare.

Fortunately, for travelers like me who want to explore beyond the city without roughing it, touring options are becoming more plentiful and cushier. Established outfitters like Abercrombie & Kent and Mountain Travel Sobek, which have offered bespoke or occasional trips there in the past, now run several group trips each year. The company I chose, Cox & Kings, arranged a guided itinerary for me, and two other American tourists, that took in three distinct regions of the country: a bustling hub, a frontier town and a far-flung jungle community. We stayed in three comfortable lodges, flew from place to place in bush planes and met new guides in each region.

Our first few days were spent in Mount Hagen, a lively mountain town with open-air markets abundant with produce. We stayed at Rondon Ridge, a newly renovated lodge that accommodated a Rolling Stone a few years back, so our guide, Michael, eagerly told us. As with Port Moresby, Mount Hagen, with its paved roads and cell towers, looked more modern than I had expected, but on excursions from the lodge to nearby villages, we learned that deep-rooted traditions continue to hold sway.

Most local residents still live in bamboo-thatch huts, go barefoot, and till their coffee and sweet-potato fields with hand tools. We saw ceremonial dance performances that enacted tribal legends, the spookiest performed by “mud men” in baked-clay, helmet-like masks. We also met farmers who had paid exorbitant bride prices (usually in pigs) for their multiple wives. One day we came across a solitary hut in the forest, not far from a modern medical clinic, where a man in a bark-cloth apron and feather headdress sat silently: a spirit doctor, holding office hours.

Our next stop was Tari, a high-mountain town that’s been a home base, since the early 2000s, for a number of mining, oil drilling and natural-gas pipeline projects. There, the indigenous customs seemed much more fraught. Amid Tari’s misty peaks and thunderous waterfalls live many of the local Huli people, whose cultural rituals are among the island’s most colorful—no small claim. Local “wigmen,” for example, sequester themselves for years at a time to grow, and then ceremonially harvest, their hair—which is used, along with feathers and bird wings, to make elaborate wigs that sell for great sums among other Huli men.

Other tribal codes in Tari, though, were far more unsettling. It turned out we’d arrived just as a long-simmering conflict between local clans had escalated to violence. The clash, according to our hosts at Ambua Lodge, the lushly landscaped, walled-in compound where we stayed for three days, ignited over land rights. My companions and I were warned not to stray off the lodge property, except on guided minibus trips to visit other villages. On these rides, we passed crowds of tribesmen patrolling the roadways—all carrying machetes, axes or homemade single-shot rifles that had been cobbled together from scrap metal and steel pipe.

I was more than a little freaked out by the time we arrived in the remote Karawari River valley, our final destination. The Iatmul people there had, for centuries, stayed mostly cocooned from the outside world. They had also once been some of the country’s fiercest headhunters.

My unease lifted soon after we landed. Life along the wide, mud-colored river seemed the picture of serenity. Motoring in a small launch on our first day, I spied smoke rising from palm-roofed riverbank homes, fishermen drifting quietly in their dugout canoes.

Over the next few days, we visited local villages along the riverbank, where we found residents weaving fish baskets or grinding sago-palm flour. But not everything in the Karawari was idyllic. We met teenagers whose backs were patterned with raised “crocodile” scars from painful initiation ceremonies, and came across village “blood stones,” stone pillars, which half a century ago warriors would decorate with the severed heads of their enemies.

On my last evening, over beers at Karawari Lodge with another guide, Chris, I asked him a question I’d been pondering: Could Papuans still maintain their traditions, with more new-world emissaries like me turning up? “I can only speak for myself,” he said. “But I can tell you my culture is strong inside me. It always will be.”

Just then, a twinkly arpeggio issued from his back pocket. Frowning, he pulled out a flip phone—the first I’d seen on the Karawari. “Sorry,” he said. “I need to take this.”

The Lowdown: Going Off-the-Grid in Papua New Guinea

Getting There: Flights to Port Moresby depart daily from Sydney and Brisbane (flights times are between three and four hours), and several times weekly from Singapore, Hong Kong and Manila. From Port Moresby, domestic carriers Air Niugini and PNG Air fly to smaller towns, such as Mount Hagen and Tari. The Karawari River valley can only be accessed by charter flight. Several tribes don’t take kindly to trespassers, which means it generally isn’t safe for travelers to trek or camp independently in undeveloped parts of the country. It’s wiser to book a guided itinerary through a reputable international operator such as Cox & Kings (9-day tour from $6,595 a person for a group of up to 20 people, coxandkingsusa.com) or Mountain Travel Sobek (11-day tour from $5,950 a person for a group of four or more, mtsobek.com).

Staying There: Trans-Niugini Tours, which partners with most foreign tour companies, operates comfortable wilderness lodges throughout the country (including Rondon Ridge, Ambua Lodge and Karawari Lodge). The lodges provide guided nature treks and visits to local villages, meals and fairly modern accommodations.

What to Bring There: Since the weight limit for luggage on charter flights is 22 pounds, pack less clothing than you think you’ll need (and plan to wash your clothes along the way—all the lodges mentioned above offer laundry service). Strong bug repellent, to protect against mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and Zika, is a must. Don’t bother bringing your smartphone or at least switch it off during most of your trip; outside of Port Moresby, reception and Wi-Fi are rare.