There are bats hanging over my bed.

I discover them the morning I arrive at Shompole, when I’m escorted to my private sleeping loggia, which can’t quite be called a room because it has no walls. The sheets on my king-size bed are freshly ironed, eucalyptus-scented, and cooled by a solar-powered fan, but all that separates them from the surrounding landscape—a sweeping panorama of East African veld, thorny scrub, and sky—is a framed cube of mosquito netting and a steep thatched roof.

A riot of squeaking and fluttering ensues from above as I heft my suitcase onto the bed. I look up, and there they are: about a dozen small, mouse-colored bundles suspended from the rafters like crumpled handkerchiefs. As I watch, one bundle twitches and extends a long filmy wing before rewrapping itself.

A riot of squeaking and fluttering ensues from above as I heft my suitcase onto the bed. I look up, and there they are: about a dozen small, mouse-colored bundles suspended from the rafters like crumpled handkerchiefs. As I watch, one bundle twitches and extends a long filmy wing before rewrapping itself.

“The bats are good,” says David, a tall young Masai I meet in the main lodge, when I describe my unexpected bunkmates. “They are yellow long-eared bats. Vesper bats. That means they eat mosquitoes.”

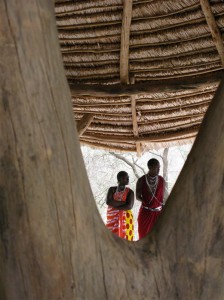

David’s dressed traditionally—draped in a bright-red shuka, with beaded cuffs encircling his slender wrists—and speaks in elegantly enunciated English. Pausing for a moment from his job of setting the long communal table, he gestures at the chirping swallows that dart above our heads among the ceiling beams.

“Birds eat mosquitoes, too. Do you like birds?” he asks. He leads me to the edge of the dining terrace and spends the next several minutes pointing out some of the species fluttering in the nearby treetops: a needle-nosed, iridescent green malachite sunbird; a speckled mousebird with a tail as long as my forearm; a band of electric-yellow masked weavers—which, David says, knit their delicate, straw-globe nests on the frailest tree branches, so predators won’t be able to reach them.

“Birds eat mosquitoes, too. Do you like birds?” he asks. He leads me to the edge of the dining terrace and spends the next several minutes pointing out some of the species fluttering in the nearby treetops: a needle-nosed, iridescent green malachite sunbird; a speckled mousebird with a tail as long as my forearm; a band of electric-yellow masked weavers—which, David says, knit their delicate, straw-globe nests on the frailest tree branches, so predators won’t be able to reach them.

Heading back to his plates and silverware, David glances at me over one blade-thin shoulder. “At night there is a genet cat that sometimes comes to the rooms,” he says. “He may walk right past your bed. And vervet monkeys—they like to steal soap from the bathroom.”

My eyes widen, and a bemused expression crosses his face.

“Yes, we are very close to the animals here,” he says. “Isn’t that why you have come?”

**

My answer to David’s question is, yes and no.

Yes, it’s thrilling to be here, on the Nguruman Escarpment along the southernmost edge of Kenya—specifically, on the 40,000-acre, relatively unknown expanse of the Shompole Conservancy. Animals don’t congregate here in thick herds, as they do in Masai Mara National Park, 70 miles to the northwest. Yet it’s still possible to drive across the open veld and suddenly spot a pair of giraffes languidly unbowing their necks above the acacia trees. Or a troupe of zebra, their stripes shimmering in the heat like a mirage; or a trio of startled impala doing grand jetés over the high desert grass.

But the proximity to Africa’s fauna isn’t what interests me most about Shompole. Rather, it’s the close, ubiquitous presence of the Masai—those other, deep-rooted inhabitants of the Rift Valley, whose culture is often co-opted by, but not especially synergic with, the safari tourism industry.

Most Kenyan and Tanzanian safari lodges enlist Masai—traditional pastoralists, but with a fierce hunting history—as game drivers, security guards, and after-dinner entertainers (their high-jumping dances are meant to display virility). But Shompole ascribes to a radically  different business model. Here, 70 percent of the staff—including the chefs, the safari guides, the jeep mechanics, and the gardeners who grow the vegetables and herbs used in the kitchen—come from local Masai settlements. More remarkable, the tribe members aren’t just employees of Shompole: they have a 30 percent ownership stake in the property.

different business model. Here, 70 percent of the staff—including the chefs, the safari guides, the jeep mechanics, and the gardeners who grow the vegetables and herbs used in the kitchen—come from local Masai settlements. More remarkable, the tribe members aren’t just employees of Shompole: they have a 30 percent ownership stake in the property.

The unusual partnership was the brainchild of Shompole founder Anthony Russell, a Kenyan-born artist and conservationist who first visited the Nguruman Escarpment in 1999. Moved by the beauty of the landscape and troubled by the plight of the local Masai (who had been devastated by years of drought), Russell approached the elders of the local clans with a proposition to lease a parcel of the 140,000-odd acres under their tribal stewardship. With their grazing lands parched and their cattle herds dwindling, they quickly recognized the potential benefits of Russell’s vision: a cooperatively run lodge that could bring new visitors—and new wealth—to their valley, while allowing them to maintain their traditional way of life.

Ten years on, it’s clear that the experiment has succeeded. Shompole has provided local  Masai with some $3 million in earnings and land conservation fees—allowing their settlements to thrive and hundreds of their children to attend schools and colleges. The tribe’s renewed commitment to managing the land has paid off ecologically as well. Ten years ago, only a handful of starving animals occupied this part of the valley, including just four or five lions. Today, thanks to the unprecedented efforts of Shompole’s Masai landowners to limit livestock grazing and forgo their ancestral custom of game hunting, 68 lions now live on and around the conservancy.

Masai with some $3 million in earnings and land conservation fees—allowing their settlements to thrive and hundreds of their children to attend schools and colleges. The tribe’s renewed commitment to managing the land has paid off ecologically as well. Ten years ago, only a handful of starving animals occupied this part of the valley, including just four or five lions. Today, thanks to the unprecedented efforts of Shompole’s Masai landowners to limit livestock grazing and forgo their ancestral custom of game hunting, 68 lions now live on and around the conservancy.

Masai influence is everywhere at Shompole: in the traditionally beaded textiles and upholstery, the iron spears planted upright in doorways to indicate “do not disturb,” the voices of staffers murmuring to one another in their native tongue, Maa.

But the most dramatic, and fabulous, manifestation of the tribal collaboration here is the indigenous-chic architecture. The structures (housing 24 open-air suites, all designed by Russell) are made from the same materials as the huts in nearby villages: white quartz, fig  branches, river rock, straw. Rough-textured, with curving surfaces punctuated by pools of water, they seem to have grown organically, like mushrooms, out of the red-rock cliffs and brushy slopes of the escarpment. Yet when they’re seen from above, the lodge’s cluster of soaring thatch spires seems as modern a silhouette as the Sydney Opera House or Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim. It’s almost certainly been a draw for the small parade of celebrities who’ve stayed here in recent years (Bono and Bill Gates among them).

branches, river rock, straw. Rough-textured, with curving surfaces punctuated by pools of water, they seem to have grown organically, like mushrooms, out of the red-rock cliffs and brushy slopes of the escarpment. Yet when they’re seen from above, the lodge’s cluster of soaring thatch spires seems as modern a silhouette as the Sydney Opera House or Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim. It’s almost certainly been a draw for the small parade of celebrities who’ve stayed here in recent years (Bono and Bill Gates among them).

The bats in my roof make a racket as I’m getting ready for bed. They’re growing restless now that the sun has gone down—rustling their wings, flapping and twittering. For a while I listen to them as I lie inside my gauzy mosquito net, until gradually the sounds grow softer, and I sleep.

**

Game scouting with Issa at the wheel feels a little like riding with a brand-new stick-shift driver: there are a lot of abrupt lurches and shuddering stops. It takes a while before I figure out that Issa, who is piloting the car forward but craning his heavily beaded neck out the side window, is tracking. When he sees something—the cloven hoofprint of a giraffe, a kudu-shaped depression in the dirt, a freshly laid turd—the jeep bucks to a halt. Once he’s assessed the situation, off we go again in herky-jerky pursuit.

I’ve grown fond of Issa over the past couple days. Yesterday, he’d taken a group of guests to visit a local Masai village, which included a look into the homes of Shompole’s part owners. I had ducked through the baked-mud doorway of a hut and into thick, smoky darkness, lit only by embers of the hut’s fire pit. Encouraged to sit on the occupants’ bed (a straw pallet covered in cowhides), I had listened as Issa pointed out where everyone—including the goats—slept.

Earlier this morning, he’d accompanied another group of us on a bush walk, along a dry riverbed shaded by fig trees. On the way, he’d imparted traditional bush medicine tips—how certain brewed plants could treat dysentery; how the pulverized bark from a particular tree drew poison from a snakebite. But he’d also talked at length about his own personal life: about his one wife and two girlfriends (Masai men are polygamous); about what men in his village bartered in order to marry (cows, blankets, and, in his own case, a jug of home-brewed liquor). Most unsettlingly, he’d spoken about how Masai women (or “mamas”) are customarily treated as beasts of burden.

“Our women, they have no rights,” Issa had said, a little sheepishly. “They build our houses, raise our children, fetch wood and water. But they make no decisions. That is for the men.

“This is changing,” he’d said. “But it will take a long time, because it is in our culture.”

So, apparently, is tracking game. Issa has stopped the jeep and is peering down at the dusty ground.

“Lion,” he says, pointing to a vaguely circular dent in the dirt. I’m skeptical; the entire valley is pockmarked with such ambiguous divots. But Issa floors it and we’re off, bumping across the scrubby plain, which extends so flatly in every direction it couldn’t possibly hide a lion.

“Lion,” he says, pointing to a vaguely circular dent in the dirt. I’m skeptical; the entire valley is pockmarked with such ambiguous divots. But Issa floors it and we’re off, bumping across the scrubby plain, which extends so flatly in every direction it couldn’t possibly hide a lion.

Except—suddenly—there one is. A young male, tawny and lithe, crouching in the lee of a thorned shrub. His amber eyes follow us as Issa slows the jeep to a crawl.

As we creep closer, the lion rises and takes a few challenging steps away from the shrub. That’s when we see he’s not alone—there are two other lions, the same size and shape as he is, lolling in the meager shade. They’re barely grown cubs, Issa tells us in a low voice. Siblings. They’re maybe eight or nine months old, young enough that we can still see camouflage spots on the fur of their bellies.

We watch the lions, the lions watch us. Insects hum. Minutes pass. And then, at once, Issa accelerates and we careen away, the lot of us flushed and exhilarated by what we’ve just seen.

As we head back for what will be my final night at Shompole, I think about something I remember Issa mentioning on that morning’s walk.

“Hey,” I say, leaning forward toward the driver’s seat. “Didn’t you say that Masai used to be lion hunters?”

Issa’s copilot, Daniel, turns to answer me from the passenger side.

“Once,” he says. “But no more.”

Daniel’s face breaks into a wide, gap-toothed grin.

“Now the lions are our friends,” he says. “Like you!”

**

Shompole has its own private airstrip, accessible via 30-minute charter flight from Nairobi Airport. Rates per person, per night start at $630. Since the lodge is close to other wildlife-rich areas (including Masai Mara and Amboseli national parks), many guests choose to incorporate a stay at Shompole into a larger bespoke safari itinerary, like those offered by Micato.