When our dive boat captain cut the engine, just east of the island of Mayreau, we lurched for a few minutes in the cyan waters as we prepared to jump overboard. Beneath our hull, our small group had been told, were Mayreau Gardens, a sweep of coral reef massed with gorgeously colored sponges and vibrant sea life, and one of the most beautiful dive sites in St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

When our dive boat captain cut the engine, just east of the island of Mayreau, we lurched for a few minutes in the cyan waters as we prepared to jump overboard. Beneath our hull, our small group had been told, were Mayreau Gardens, a sweep of coral reef massed with gorgeously colored sponges and vibrant sea life, and one of the most beautiful dive sites in St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

Despite the ease of the half-hour trip that had brought us here from the private-island resort of Petit St. Vincent, I was jittery. This would be my first scuba dive in almost 20 years, and my stomach wasn’t happy about it. As I leaned over the bulwark of the boat, trying to ease my nausea, a chiding, French-inflected voice floated over to me.

“My dear, are you going to feed the fishes?” it asked. “Or shall we jump in and see them?”

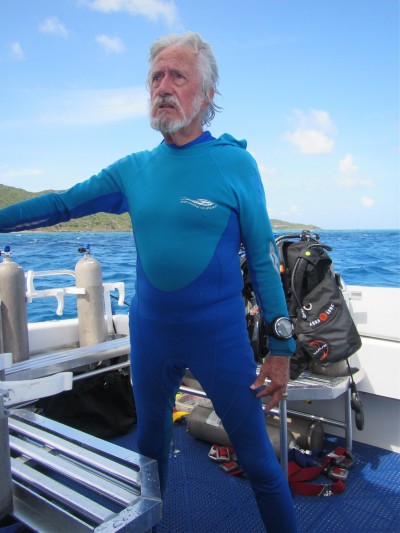

Raising my head, I faced the speaker: a slender, bearded 70-something man in a zippy turquoise wet suit, dark eyes twinkling beneath a windblown mop of white hair.

“I’ll feel better once I’m in the water, right?” I asked uneasily, pulling my mask onto my head and shrugging into my buoyancy vest.

“Of course, you will,” said the man, chucking me affectionately under the chin. “Everything is better in the water!”

Since the man was Jean-Michel Cousteau — the oldest son of Jacques, and the person said to have logged more years underwater than any other living soul — I took the remark as gospel. When a Cousteau speaks about the water, you listen. So I tucked my regulator into my mouth and leapt into the Caribbean.

Since the man was Jean-Michel Cousteau — the oldest son of Jacques, and the person said to have logged more years underwater than any other living soul — I took the remark as gospel. When a Cousteau speaks about the water, you listen. So I tucked my regulator into my mouth and leapt into the Caribbean.

It’s hard to remember now, in these days of ubiquitous GoPro footage, how miraculous it was back when “The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau” appeared on television in the late 1960s and early ’70s. The show provided a glimpse of the fantastic creatures and ecosystems that lived beneath the ocean’s surface, quite literally opening up a new world to my generation and those that followed.

Since Jacques’s death in 1997, the Cousteau legacy has been maintained and advanced by his children and grandchildren, who have started several nonprofit organizations that promote marine education and conservation. Our dive was part of Jean-Michel’s latest attempt to open a less virtual world to a new audience: a Caribbean dive center based at Petit St. Vincent, which had opened in November.

One of the reasons I’d been out of underwater commission for so long was the deluge of depressing news I’d read over the years, specifically about the degradation of the world’s reefs. The problem seemed particularly concentrated in the Caribbean, because of rampant coastal development and overfishing as well as climate change. According to a major report released in July by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and the United Nations Environment Programme, surveys conducted at almost 100 Caribbean locations showed a 50 percent decline in corals since 1970. Another report, released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in August, lists all 20 of the most abundant coral species in the Caribbean as threatened.

At first glance, the offerings at the Jean-Michel Cousteau Diving Caribbean center don’t seem especially different from those at other island resorts. Staff members at the Petit St. Vincent headquarters run scuba-certification courses for both beginner and advanced divers, and also more limited classes that let adults and children as young as 8 try scuba in a carefully controlled environment: off a sandy beach and beneath a boat pier, where trumpet fish hover and feathery-antlered Christmas-tree worms festoon the pilings.

Meanwhile, every day, a gleaming boat called L’Aventure takes experienced divers among more than a dozen still-flourishing local sites, including the Tobago Cays, a protected preserve for endangered green sea turtles. Resort guests can choose to pay for a single dive (starting at $85 for a one-tank excursion) or multiday packages; a three-day package of daily one-tank dives, for example, costs $235.

But there’s a larger agenda at work. Beyond simply guiding Petit St. Vincent’s resort guests to appreciate the local underwater sights, Mr. Cousteau envisions the center functioning as a hub for educational outreach into local island communities. Along with partners at his nonprofit organization, Ocean Futures Society, he is developing a program to arrange visits with schoolchildren from surrounding islands. (St. Vincent and the Grenadines, a country comprising more than 32 main islands and a number of uninhabited specks, has an economy that largely depends on tourism.)

“My father always said that people will protect what they love,” Mr. Cousteau told me over dinner the evening before our dive at Mayreau Gardens. “But what I believe is that people only love what they understand. So that is what we strive for: to help people here to better understand this precious resource, the ocean. And to enlist their help in treating it gently.”

“My father always said that people will protect what they love,” Mr. Cousteau told me over dinner the evening before our dive at Mayreau Gardens. “But what I believe is that people only love what they understand. So that is what we strive for: to help people here to better understand this precious resource, the ocean. And to enlist their help in treating it gently.”

The first order of business, he said, is to hire a naturalist, ideally a Caribbean native, to manage the resort’s educational programs. (Since he spends much of his time traveling around the world to film undersea documentaries and speak about ocean conservation, he will be on-site himself only a few times a year.)

A more focused, but just as ambitious, aim of the center is the morphing of the entire 115-acre island resort into a model of sustainability — one that’s inspired by coral reefs, the systems that govern communities under the sea.

“There’s almost no waste on a coral reef,” explained the marine biologist Richard Murphy, who has worked with the Cousteau family since 1968, and consulted extensively with Phil Stephenson, the owner of Petit St. Vincent, about “greening” the island. “Almost everything — structures, raw materials — is recycled, and every organism fulfills some sort of job that benefits the community. It’s basically a solar-powered machine that runs for free and repairs itself.”

While that sort of utopian-sounding colony may be difficult to replicate at a high-end resort — particularly one where amenities like air-conditioning and bottled water are expected — Mr. Murphy said, Ocean Futures Society and Petit St. Vincent are committed to the efforts.

Low-impact tourism seems a good fit for the island’s mellow character. The resort, which was first developed in 1968, in many ways still feels pleasantly trapped in time. Though its 22 free-standing guest cottages, spread around the periphery of the island, have been modernized, they still feature their original island-sourced, hand-built stone walls. There’s no Wi-Fi or phone service in the cottages (although there is one spot, at the resort’s hilltop office and restaurant, where you can connect). When guests want food delivered or a ride in one of the resort’s vintage Mini Mokes, they raise a flag at the end of their cottage’s walkway.

Behind those quiet charms, though, the resort has been making sustainability advances in ways harder to see. Over the last two years, Mr. Stephenson — who took over the resort in 2010 and first reached out to Mr. Cousteau in 2013 — has made significant changes to island operations. Among them are the installation of a water-bottling facility, which has eliminated 90 percent of the single-use plastic previously used at the resort. He has also set up a reverse-osmosis/desalination plant to provide both running water and irrigation for the resort gardens, where much of the produce used in the kitchens is grown.

Undertaking these changes — and there are many more afoot — wasn’t just a matter of encouraging sustainability, Mr. Stephenson told me. “It was a business decision, too,” he said.

“I have to say, when the Ocean Futures people showed me that I could save $70,000 a year using glass rather than plastic bottles on the island,” he explained, “making that shift was a no-brainer.”

The next day, during my dive trip at Mayreau Gardens with Mr. Cousteau, I felt my initial sense of trepidation disappear as soon as I submerged. Mr. Cousteau hovered at my side like a lanky Poseidon, beard and hair drifting in the current; I followed him, entranced, as he pointed out a grove of waving sea fans, a lionfish lazily fluttering its spines, and a shy, barely visible spotted moray eel — all creatures whose names I had surely learned from watching his father on television, almost a lifetime ago. He had been right, of course: Everything is better in the water.